After taking a blogging hiatus, it seems appropriate that I pop back in on the anniversary of Pearl Harbor. I have to admit that I was shocked to discover that it was the 70th anniversary of the attack, which left more than 2,400 American servicemen dead. Writing about World War II makes the attack feel so much more recent and relevant in my mind, so much so that it was a bit shocking to find that today’s anniversary isn’t getting more press. Oh, it’s being mentioned in the news, but when you consider what a drastic role Pearl Harbor had in changing the course of American History, it seems awfully strange that it gets less ink that the Kardashian’s latest antics.

After taking a blogging hiatus, it seems appropriate that I pop back in on the anniversary of Pearl Harbor. I have to admit that I was shocked to discover that it was the 70th anniversary of the attack, which left more than 2,400 American servicemen dead. Writing about World War II makes the attack feel so much more recent and relevant in my mind, so much so that it was a bit shocking to find that today’s anniversary isn’t getting more press. Oh, it’s being mentioned in the news, but when you consider what a drastic role Pearl Harbor had in changing the course of American History, it seems awfully strange that it gets less ink that the Kardashian’s latest antics.And what were those changes? Of course, we, as a nation, left our position of neutrality over the war and entered the fray, full tilt. This was a gross miscalculation on Japan’s part. They already knew we had greater capacity for war production and that the odds were good we could defeat them, but by attacking us on our own land, they awoke a beast so desperate for vengeance that nothing would satisfy us but complete victory. Or as Japan’s Fleet Admiral put it, "I fear all we have done is awakened a sleeping giant and filled him with terrible resolve.”

But how else did it change us?

- No longer did we consider the home front safe. After years of watching wars from a distance, we had to conclude that an enemy could strike on American soil at any time, a lesson that we, sadly, learned again on September 11th.

- Prior to Pearl Harbor, we were hardly enthusiastic about entering the war, but after the tragedy many people changed their opinions of the necessity of joining the fray. Pearl Harbor gave us a rallying cry and a convenient piece of home front propaganda to wave around as the war lingered on, we tired of the loss of life, and the restrictions on resources. No matter how self-centered you were, it would be hard not to soldier on when you were reminded of the tremendous sacrifices those who were at Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941 made.

- Just as the U.S.’s policy of isolationism ended with our entry into the war, so, in some ways, did the isolation of her citizens. Faced with such tremendous loss, we enlisted, volunteered our time, gathered resources, and looked for other ways to band together as a community for the greater good.

- Pearl Harbor helped to instigate one of America’s favorite past times, the government conspiracy theory. Long before we obsessed over aliens landing in Roswell or the government ordering the attacks on 9/11, the American public questioned how much we knew or didn’t know about the attack on Pearl Harbor in the days before it happened.

- The attack gave us an enemy to hate unequivocally. From the language used to describe the attack (“Sneaky”) and the caricatures of Japanese people in the media to the deportation and internment of 100,000 people of Japanese descent, Pearl Harbor gave Americans permission to hate an entire nation of people because of the actions of a few. It was an unfortunate blueprint for the ways in which we would respond to people of Middle Eastern descent after 9/11.

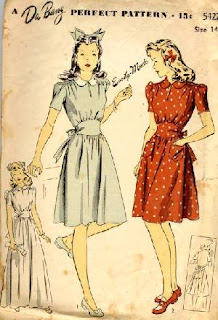

And, of course, perhaps the most dastardly thing about Dec. 7, 1941, is that it spawned this: